Is Guyana susceptible to the natural resource curse?

By

Joel Bhagwandin

Recently, a Jamaican economist argued that “Guyana could fall victim to the so-called ‘resource curse’ as it moves deeper in developing its oil and gas finds because it lacks strong institutions to prevent corruption. The economist went on to make some other outlandish and callous remarks wherein he argued that “Guyana is going to go nowhere,” political parties will soon start to squabble over the spoils to the detriment of the country, and that unless there are strong institutions―corruption and violence will ensue, etc.

Notwithstanding, the concerns raised by the economist present an opportunity to stimulate some meaningful and critical discussion and analysis on the topic―though, unfortunately, he failed in so doing as an economics lecturer―who lectures at the premier tertiary level educational institution in the Caribbean community.

What is the resource curse?

The paradoxical resource curse is essentially a theory that describes countries with oil or other natural resource wealth―that have failed to grow more rapidly than others without. Wright and Czelusta (2004) contended that the resource curse hypothesis seems anomalous since, on the surface, it has no clear policy implication but stands as a wistful prophecy. The authors argued that countries afflicted with the “original sin” of resource endowments have poor growth prospects.

How weak is weak?

To assert that Guyana’s public sector institutions are weak―is a subjective notion rather than an inference derived from an objective analysis of the evolution of public sector institutions in Guyana over time.

Historical overview of public sector institutions in Guyana

There was a study done in 1994 titled “improving Guyana’s public sector policy implementation capacity to facilitate private investment: an institutional analysis and technical assistance strategy.” This study presented a comprehensive analysis of the state of public institutions in Guyana almost three decades ago. In the report’s introduction, it was stated that “Guyana has only recently begun to emerge from the effects of more than 20 years of state-led socialism following independence from Great Britain in 1966. Guyana’s leadership closely controlled all economic activity, either directly through state-owned enterprises or indirectly through tight price, credit, and foreign exchange controls. The cost of economic mismanagement has been high: weak economic growth (less than 1% per year during 1966-89), massively deteriorated physical infrastructure, capital flight, lack of investment, a significant “brain drain” of human resources, increasing poverty, and a huge accumulation of debt compounded with debt servicing arrears. By the late 1980s, Guyana faced a crisis that its socialist leaders could no longer address with stopgap remedies. Fundamental changes in development strategy were called for, and the Government of Guyana (GoG) turned to the international financial institutions for help”.

The report noted that by 1994, “Guyana has been quite successful in turning the economy around over the past five years (1989-94), largely due to reforms that eliminated the system of government controls that restricted economic activity”. Another important element in facilitating the expansion of private sector investment, according to the report, was the public sector investment program (PSP), which intended to provide the necessary supportive infrastructure to make private investment both effective and, ultimately, profitable. Evidently, the 1994 study has shown that the public sector institutions in Guyana had undergone a complete overhaul in the early 90s, naturally to facilitate the transition from a socialist, centrally command economy to a market economy following the implementation of the Economic Reform Programme (ERP).

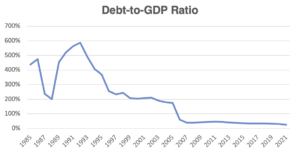

Another important point to note is that historically―during the socialist years that span some two decades, Guyana had, in fact, been a victim of the paradoxical natural resource curse―under the stewardship of the former government based on the foregoing description of the economic and political state of the economy at that time; which ultimately resulted in Guyana becoming a bankrupt state (as shown in the chart below).

Source: Bank of Guyana Reports/Author’s Calculation

It is the incumbent government that successfully reversed the economic prospects of the economy, inter alia, successfully steering the economy out of bankruptcy to economic stability―two decades later. Worthy of note is that this outturn could not have been achieved over the years without the consistent improvement and strengthening of public sector institutions to facilitate the buoyant and broad-based growth of the economy even before the discovery of oil.

Efforts have been made over the years to strengthen our public sector institutions, and the government continues to make the necessary investments. This is paramount. Two major challenges inherently characterize the weaknesses of public sector institutions, namely, human resources and employment of a modern Information Technology (ICT) framework within and across the public sector. The human resources limitations are largely attributed to our historic political and economic challenges wherein there was a lack of opportunities for our people who migrated by the thousands over the last few decades (the brain drain syndrome).

That said, of importance to note is that with the same institutions, it [evidently] depends on which political party is in government that knows how to competently derive the optimum results from these institutions. For example, let’s look at housing: the former government only delivered 7500 house lots in their entire five years term which translates to 1500 per annum. On the other hand, the current government―with the same ministry, and the same human and physical resources, delivered 21,000 house lots and turn-key homes in just over two and half years, which translates to 7,500 per annum―or 5 times more than the former government achieved in their entire five-year term.

Moreover, though the former government delivered 7500 house lots in 5 years, they did not have a proper housing program nor deliver any proper turn-key homes. Instead, the former government experimented with the ‘duplex’ concept, which failed miserably. In this regard, the former government failed to recognize that it would be difficult for any bank to finance the purchase of a duplex and for any insurance company to provide fire insurance coverage―because the design concept necessitated a special legislative framework (which was absent) to enable the banks to collateralize the units and the same for insurance.

Similarly, the same can be said for the other ministries and government agencies responsible for the processing of permits and other forms of approval and applications, which, under the former government, held up billions of dollars in investments that were subsequently unlocked following the change of government in 2020.

In the final analysis, there are inherent institutional limitations that are being addressed on an ongoing basis, and at the same time, despite the limitations, much is achieved as well with the perseverance and hard―around the clock work by the policymakers and the public servants.

There is no denying, however, what constitutes our developmental challenges and limitations. I think we have a deep appreciation and understanding of these realities and a deep understanding of what needs to be done―which is being done tangibly.

On the institutional strengthening side of things, several institutional reforms and capacity-building programs are being undertaken (too many to mention), such as improving the audit capacity of the Guyana Revenue Authority (GRA), the Auditor General’s Office, Ministry of Natural Resources and other government agencies, investment in the information technology infrastructure to modernize the entire public sector―that will aid the overall improvement in the provision of public goods and services efficiently; and thereby improving the ease of doing business. There is also the creation of new institutions to manage the oil and gas sector, such as the Local Content Secretariat, the Petroleum Commission, which will be established in due course, etc. These are just a few examples of some of the institutional capacity-building programs that the government is actively undertaking―but which will take time and resources to develop.

Conclusion

With all of the foregoing in mind, Guyana is not susceptible to the natural resource curse. The economist’s assertion that Guyana will suffer the natural resource curse because of weak institutions is highly unmeritorious and unscholarly. More so, when in fact―the incumbent government has a proven track record of successfully delivering the Guyanese economy out of a historical era of the natural resource curse. The incumbent government has demonstrated, drawing from its successful track record of good economic management, that it is pursuing the right type of economic policies and undertaking the much-needed investment in the economy―specifically in addressing the country’s infrastructure deficit, human resources constraints, education, and health care, energy and food security at the regional level, and ICT to name a few, that will enable the economic transformation to take place from a primary producing economy to a tertiary producing economy.

______________________

https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNABQ757.pdf.

About the Author

Joel Bhagwandin is a financial, economic, and public policy analyst―and an entrepreneur with more than fifteen years’ experience in the financial sector; corporate finance; financial management; consulting, and academia. He is actively engaged in providing insights and analyses on a range of public policy, economic and finance issues in Guyana for the past 6+ years. He has authored more than 300 articles covering a variety of thematic areas. Joel has also written extensively on the oil and gas sector. Academically, Joel is the holder of an MSc. in business management with a specialism in banking and finance from Edinburgh Napier University. He is currently pursuing his second and third masters: 1) MBA (Finance) (Top-up) through Edinburgh Napier University, and 2) MSc. in Finance (Economic Policy) through the University of London.