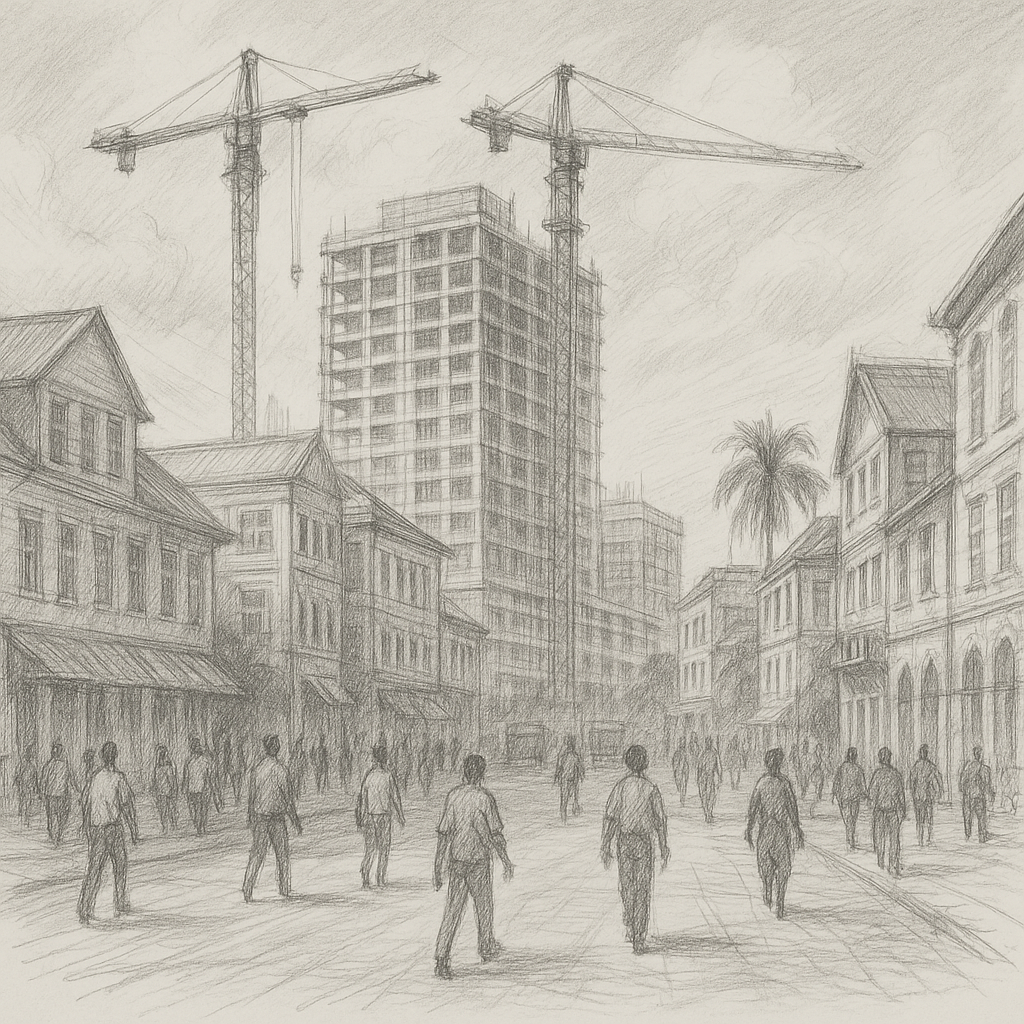

Georgetown, Guyana — The streets of this colonial capital hum with an energy that wasn’t there five years ago. Construction cranes pierce the skyline, luxury hotels are rising from empty lots, and the conversation in Georgetown’s rum shops has shifted from emigration to investment opportunities. It’s the sound of a nation transforming overnight—from one of South America’s poorest countries to potentially one of its richest.

The catalyst? Oil. Lots of it.

Since commercial production began in late 2019, Guyana has emerged as the world’s newest energy superpower, pumping 645,000 barrels per day as of early 2024 from offshore fields that hold over 11 billion barrels of recoverable reserves. For a nation of just 800,000 people, it’s a windfall of almost incomprehensible proportions.

But here’s the twist: This oil boom is happening just as the world embraces nuclear power and accelerates away from fossil fuels. At December’s COP28 climate summit in Dubai, nuclear energy was formally recognized in a UN climate agreement for the first time in history, while countries pledged to triple nuclear capacity by 2050. Meanwhile, Guyana—long a champion of forest conservation and climate action—finds itself pumping the very commodity the world says it must abandon.

“The question is whether we can become an oil producer and still maintain our environmental credentials,” says Vice President Bharrat Jagdeo, “and we believe the answer is yes.”

It’s a bold claim that places this tiny South American nation at the center of one of the most complex debates of our time: Can fossil fuel wealth and climate leadership coexist?

The scale of Guyana’s oil discovery is staggering by any measure, but for a country this small, it borders on the surreal. The petroleum industry drove a 62.3 percent GDP growth in 2022, the highest globally according to the IMF. The economy has tripled in size since oil production began, with GDP per capita increasing from one of the lowest in Latin America in the early 1990s to US$18,342 in 2022.

The consortium behind this transformation—ExxonMobil with a 45% stake, Hess Corporation holding 30%, and China’s CNOOC controlling 25%—operates from the massive Stabroek Block, a deepwater field that made more than 30 discoveries since 2015. Current production comes from three floating platforms with names that sound almost mythical: Liza Destiny, Liza Unity, and Prosperity.

“We are already producing above our initially estimated capacities,” Alistair Routledge, ExxonMobil Guyana’s president, announced in February. All three platforms are pumping about 160,000, 250,000, and 230,000 barrels per day respectively—numbers that would be impressive for countries ten times Guyana’s size. The projections are even more dramatic. By the end of 2027, combined production capacity is expected to reach approximately 1.3 million barrels per day, which would make tiny Guyana the second-largest oil producer in South America after Brazil.

But this oil bonanza arrives at perhaps the most inconvenient moment in human history for fossil fuel producers. The world is not just talking about moving away from oil—it’s actually doing it. At COP28 in Dubai, something unprecedented happened. After nearly three decades of climate summits, nuclear power was explicitly included in the Global Stocktake for the first time, with 198 countries agreeing that nuclear acceleration was needed to achieve deep global decarbonization. The International Atomic Energy Agency has raised its nuclear growth outlook for four consecutive years, projecting capacity could increase 2.5 times by 2050 in a high-case scenario.

Meanwhile, 413 nuclear reactors operated worldwide as of December 2023, generating about 10 percent of global electricity and a quarter of all low-carbon electricity. Countries from France to China to the United States are planning new reactors or extending plant lifetimes, viewing nuclear as essential for round-the-clock clean power.

For Guyana, this global energy transition presents what economists call a “stranded assets” problem. If the world succeeds in aggressive climate action, fossil fuel demand could weaken dramatically in the 2030s, potentially leaving some of Guyana’s vast reserves worthless in the ground. “We aim to secure new sources of revenue before the energy transition to renewables reduces demand for fossil fuels,” Vice President Jagdeo acknowledged in a recent interview. The calculus is stark: extract and monetize oil wealth over the next 20 years while demand remains strong, then use those revenues to build a diversified, climate-resilient economy.

Guyana’s strategy draws heavily from Norway’s playbook, but with crucial differences that reflect both its development needs and environmental assets. Like Norway, Guyana has established a Natural Resource Fund to manage oil revenues, with parliamentary oversight designed to prevent the “resource curse” that has plagued other oil-rich nations. But unlike Norway, Guyana starts from a much lower development baseline and faces existential climate threats. Over 90% of the population lives on a low-lying coast vulnerable to sea level rise, while the country’s vast rainforests—covering 85% of its territory—represent one of the world’s most important carbon sinks.

The government’s answer to this dual challenge is the Low Carbon Development Strategy (LCDS) 2030, a pioneering policy framework that treats environmental assets as central to development planning. The strategy essentially argues that Guyana can “have its cake and eat it too”—developing petroleum resources while maintaining its status as a net carbon sink through forest conservation.

The most innovative element of this approach materialized in December 2022, when Hess Corporation agreed to purchase $750 million worth of carbon credits from Guyana over the next decade, covering 37.5 million tons of CO2 equivalent. It’s a remarkable arrangement: an American oil company effectively paying three-quarters of a billion dollars to keep Guyana’s forests standing, using the profits from oil extraction to fund conservation. “This deal goes a far way in proving that they are a global leader in accelerating ambition to reverse deforestation,” President Irfaan Ali said at the signing ceremony. Around 30% of the $750 million investment will go toward developing Indigenous Amerindian communities, which account for about 10% of Guyana’s population.

Complicating Guyana’s energy future is a geopolitical wildcard that reads like something from a Cold War thriller. Venezuela, facing its own economic crisis, has aggressively reasserted claims to Guyana’s Essequibo region—territory that encompasses much of the offshore oil fields. In late 2023, Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro announced plans to annex Essequibo, leading to military buildups and international alarm.

The dispute isn’t just about national pride. Exploration operations in the Stabroek block and nearby offshore blocks may be affected by Venezuela’s claim of sovereignty over the Essequibo region, which accounts for more than two-thirds of Guyana’s land area. A military clash could not only halt oil production but disrupt global energy markets at a critical moment in the energy transition. So far, the international community—led by the United States, United Kingdom, and Caribbean Community—has backed Guyana’s sovereignty. But the dispute remains a sword of Damocles hanging over the country’s oil dreams.

As Guyana grapples with maximizing its fossil fuel windfall, the global energy landscape is simultaneously embracing technologies the country hasn’t even considered. The nuclear renaissance gaining momentum worldwide offers both challenges and opportunities for oil-rich nations. Small modular reactors (SMRs) account for about one-quarter of the capacity added in IAEA high-case projections and 6% in low-case scenarios. These compact nuclear plants—typically under 300 megawatts—promise to deliver carbon-free power with lower upfront costs and enhanced safety features, potentially revolutionizing energy systems in smaller countries.

While Guyana has no immediate plans for nuclear power, the technology’s rapid development could theoretically offer a leapfrog opportunity. Oil revenues could finance advanced clean energy infrastructure, including SMRs that provide steady electricity without emissions. It’s speculative, but the possibility adds another pathway to Guyana’s energy future menu. “Where the world is trying to get by 2050, we are already there,” Jagdeo noted, referring to Guyana’s net-zero carbon status achieved through forest carbon sequestration. The question is whether this environmental advantage can be maintained while extracting billions of barrels of oil.

Guyana’s economic transformation has been nothing short of spectacular. After 44% GDP growth in 2024, the IMF predicts a 14% expansion this year. Oil revenues reached $2.57 billion in 2024, including crude sales and $348 million in royalties, compared with $1.62 billion in 2023. But this windfall comes with classic petro-state risks: inflation, currency appreciation that hurts other exports, and governance challenges. Guyana has instituted measures including local content laws and the Natural Resource Fund to mitigate these dangers, but the true test will come as oil revenues multiply over the next decade.

The country is already investing heavily in diversification. The Gas-to-Energy project will pipe natural gas from offshore fields to a new 300-megawatt power plant, dramatically reducing electricity costs while cutting domestic emissions. Meanwhile, solar farms and the long-delayed 165-megawatt Amaila Falls hydropower project aim to achieve 70% renewable electricity by 2035. “Oil is a catalyst for Guyana’s near-term prosperity,” explains a senior government official, “but we’re strategizing to convert this finite resource into more enduring forms of capital—human capital, infrastructure, and low-carbon economic sectors.”

Perhaps nowhere is Guyana’s balancing act more visible than in its environmental policies. The country faces the cruel irony of climate change: the oil enriching the nation contributes to the very crisis threatening its low-lying coast. Devastating floods in 2021 offered a preview of what unchecked global warming could bring. Guyana’s response has been to position itself as a responsible oil producer. New regulations require operators to reinject or utilize associated gas rather than flaring it, implement robust oil spill prevention protocols, and maintain comprehensive environmental monitoring. The specter of a major offshore spill—memories of BP’s Deepwater Horizon disaster loom large—has prompted investments in response equipment and international cooperation with the U.S. Coast Guard.

On the climate mitigation front, Guyana’s strategy is multifaceted. Forest conservation remains the cornerstone, with REDD+ carbon credits providing revenue to local communities for conservation and sustainable forestry. The LCDS 2030 framework monetizes these environmental services, with the Hess deal serving as proof of concept. Domestically, the Gas-to-Energy project will eliminate heavy fuel oil from power generation, cutting CO2 emissions by an estimated 50% in the power sector. Simultaneously, ambitious renewable energy targets aim for a dramatically cleaner electricity mix within a decade.

Looking further ahead, Guyana remains open to emerging clean energy technologies, including the small modular reactors generating excitement worldwide. While no concrete nuclear plans exist, the global development of SMRs is being watched with interest. These compact reactors—if they become commercially viable in the early 2030s—could theoretically provide steady, carbon-free power for Guyana’s grid or industrial operations. For a small nation with limited land area, SMRs might eventually complement renewables in achieving 100% clean electricity while supporting energy-intensive industries. “SMRs might eventually complement renewables in places like the Caribbean, where renewable intermittency and limited land area are challenges,” notes an energy policy analyst. For Guyana, any nuclear option remains far in the future, but oil wealth could theoretically finance such advanced technology leaps later on.

The central tension in Guyana’s story is time. The window to extract maximum value from oil may be narrower than in previous energy booms. The International Energy Agency projects that under current policies, world oil demand is likely to peak before 2030. In aggressive climate scenarios, oil use could shrink from around 90-100 million barrels per day today to under 25 million by 2050.

This timeline pressure explains Guyana’s rapid development pace. The government has approved fast-tracked production plans for multiple offshore projects and held competitive auctions for new exploration blocks, attracting bids from majors like TotalEnergies and QatarEnergy. The goal is clear: maximize oil extraction over the next two decades while global demand remains strong, using those revenues to build lasting prosperity.

Guyana’s experiment carries implications far beyond its borders. If successful, it could provide a template for how developing nations might navigate the energy transition—using temporary fossil fuel wealth to leapfrog directly to advanced clean energy systems. The model requires delicate execution: extracting resources quickly enough to capture value before demand declines, while investing wisely enough to avoid the resource curse and build sustainable alternatives. It also depends on maintaining the environmental assets—forests, carbon sinks—that provide long-term value in a decarbonizing world.

“Climate ambition and development reality must converge, not clash,” argues President Ali. “Guyana is essentially saying to the world: Help us make our development clean, and we will help you save the climate.”

Five years into its oil boom, Guyana stands at a crossroads that may define not just its own future, but the possibilities for sustainable development in an age of climate change. The stakes could not be higher—for a nation, for a region, and for the world’s understanding of how fossil fuel wealth and climate leadership might coexist.

The success of Guyana’s gamble will depend on variables both within and beyond its control: global oil prices, climate policy stringency, technological breakthroughs, geopolitical stability, and domestic governance. But perhaps most crucially, it will depend on whether the world can indeed accommodate the “right to sustainable development” of countries that contribute minimally to climate change yet suffer its worst effects.

In the humid air of Georgetown, where colonial buildings stand alongside gleaming new hotels, the future feels both promising and precarious. Construction crews work around the clock, oil revenues flow into government coffers, and policymakers craft strategies that could reshape how we think about development in the 21st century. “The next decade will reveal whether Guyana’s chosen path can serve as a blueprint for others,” reflects a senior official, watching the sunset over the Demerara River. “We’re writing a new playbook for how to stride toward a low-carbon future while lifting an entire nation’s standard of living.”

The world is watching. And waiting for answers.

Support Independent Analysis

The Guyana Business Journal is committed to delivering thoughtful, data-driven insights on the most critical issues shaping Guyana’s future—from oil and gas to climate change, governance, and development. We invite you to support us if you value and believe in the importance of independent Guyanese-led analysis. Your contributions help us sustain rigorous research, expand access, and amplify the voices of informed individuals across the Caribbean and the diaspora.

📢 Please support the Guyana Business Journal & Magazine today

Thank you for standing with us.

Dr. Terrence Richard Blackman

Guyana Business Journal

References

- Reuters. (2024, February 6). “Exxon raises Guyana’s oil production to about 645,000 barrels per day.”

- U.S. Energy Information Administration. (2024). “Guyana becomes key contributor to global crude oil supply growth.”

- Reuters. (2025, January 17). “Oil output, exports drove Guyana economy’s growth of 43.6% in 2024.”

- International Monetary Fund. (2023). “Guyana: 2023 Article IV Consultation Staff Report.”

- International Monetary Fund. (2022, September 27). “IMF Executive Board Concludes 2022 Article IV Consultation with Guyana.”

- U.S. Department of State. (2025, January 4). “2023 Investment Climate Statements: Guyana.”

- Americas Quarterly. (2025, January 16). “Guyana: A 2025 Snapshot.”

- OilNOW. (2024, February 6). “Guyana’s oil production hits 645,000 barrels per day.”

- International Atomic Energy Agency. (2024, August 20). “IAEA Releases Nuclear Power Data and Operating Experience for 2023.”

- World Nuclear Association. (2024). “Nuclear Power in the World Today.”

- International Atomic Energy Agency. (2024, September 16). “IAEA Outlook for Nuclear Power Increases for Fourth Straight Year.”

- World Nuclear Association. (2023). “COP28 agreement recognizes accelerating nuclear energy as part of the solution.”

- International Atomic Energy Agency. (2024, January 29). “Nuclear Energy Makes History as Final COP28 Agreement Calls for Faster Deployment.”

- U.S. Department of Energy. (2023, December 2). “At COP28, Countries Launch Declaration to Triple Nuclear Energy Capacity by 2050.”

- CarbonCredits.com. (2022, December 5). “Hess Signs $750M REDD+ Carbon Credits Deal with Guyana.”

- Hess Corporation. (2022, December 2). “Hess Corporation and the Government of Guyana Announce REDD+ Carbon Credits Purchase Agreement.”

- Associated Press. (2022, December 3). “Hess to buy $750 million in carbon credits from Guyana.”

- Hart Energy. (2022, December 6). “Hess Inks $750 Million Carbon Credit Deal with Guyana.”

- Mongabay. (2023, December 28). “Questions over accounting and inclusion mar Guyana’s unprecedented carbon scheme.”

- Government of Guyana. (2022). “Low Carbon Development Strategy 2030.”